By Gillian Williams

Blake was an instrumental poet during the nineteenth century, and he could arguably be considered one of the most powerful social critics because of his focus on the rampant corruption and hypocrisy that existed in the English society. In the Songs of Innocence and of Experience, he presents a dual-focus approach to man’s propensity for good and evil as viewed through the lenses of innocence and experience. While several of the poems in the first portion entitled Songs of Innocence certainly reveal an undercurrent of neglect, suffering, and miserable children, it is the poems that appear in Songs of Experience that accurately convey to the reader the hypocrisy and perversion that existed in Blake’s society, and how politics and religion exacerbated these issues. Although all the poems from Songs of Experience portray perversions of some sort or contrary states to those presented in Songs of Innocence, I think that the poems that accurately portray Blake’s keen awareness of the abuse and exploitation of children in the English society are the poems, “London,” “The Chimney Sweeper,” “A Little Boy Lost,” “The Little Vagabond,” and “Holy Thursday.” These five poems present a strong indictment against religious and political forces for causing children to suffer and weep through “mind-forged manacles,” child labor and physical abuse.

There is clear evidence of mind-forged manacles, child labor, and abuse in the poem entitled “London.” Thematically, this lyric poem lays the groundwork for all the issues that will be explored in the other poems. I think it is appropriately titled “London” not only because it bears the name of the capital city of England but considering that at the time when Blake was writing, it was the seat of England’s colonial pursuits—the very center of the decision to subjugate other nations in order to profit from their wealth. Similarly, London was also an industrial city which made significant wealth from child exploitation and from restricting its own citizens. The poem makes this statement even clearer as the speaker wanders through this thriving metropolis and is confronted by all the mind-forged manacles he sees around him. The first line of the poem, “I wander thro’ each charter’d streets” connotes restriction and repression as those in this industrial city are enclosed within and trapped in the misery and pain they are experiencing. The word charter has multiple meanings but in its most common usage, the Oxford American Dictionary defines it as “a document from a ruler or government granting certain rights [and privileges] or defining the form of an institution (105). This usage of the word charter suggests that although it makes certain rights and privileges accessible, it is at once restrictive and repressive because the government determines what rights and privileges its citizens can enjoy. With this definition in mind, even the “chartered Thames” suggests that like the people, nature’s ability to be free and uninhibited has been disrupted by governmental control.

In effect, London’s economic and political pursuits restrict the Thames, and while it does flow, it cannot do so freely because imperialism weighs it down. Similarly, as the speaker moves on from the restricted Thames, his tone takes on a more bitter and ironic tone as he encounters the dark reality of London’s suffering and weeping children— from crying “infants” and “chimney sweepers” to “youthful harlots.” (Blake, lines 6, 9, 14). To this end, the speaker’s perspective is marred by the sight of children robbed of their innocence as they bend under the weight of this repressive city. And because of his perspective, we find that what is most haunting about the poem is the desperation of the children he both sees and hears. It allows us to see the dichotomy between the speaker’s compassion, and the cruelty of religious and political figures who refuse to hear or see these weeping children who litter London’s streets. To this end, the poem suggests that the mind-forged manacles the speaker sees in London are not self-imposed or internal but are external repressions created by religious and political entities.

Likewise, the structure of the poem also reflects the manacles the speaker sees around London as well as the exploitation that causes these children to weep. While the poem has a regular rhyme scheme of ababcdcdefefdgdg, its metrical feet have some irregularities. The first two stanzas of the poem represent perfect iambic tetrameter but by the time we get to the third stanza, the pattern shifts dramatically. For example, the first line of this stanza has one foot of anapest while the rest of the line contains two feet of iambs. This disruption in the metrical feet occurs exactly at the point when the poem intensifies because the cry of the infants now morphs into the cry of the chimney sweepers. And this intensity not only creates a parallel between the infants and the sweepers, but it also emphasizes that although the children are quite young, they live in a society that forces them to work in order to survive. Yet chimney sweeping was an extremely dangerous job for these young children to undertake, especially at the time that Blake was writing. These children would often fall to their death or die from repeated exposure to toxic soot. This view can be supported by James Montgomery who argues that chimney sweepers begin this “horrid, difficult and laborious” job as “tender infants,” and often encounter “the most dreadful and fatal accidents (12-14).

So then, if sweepers had to face such dire realities, could it be that when the speaker hears the chimney sweepers’ cry, it is their final cry as they fall from the chimneys to their death? This type of interpretation is possible because the enjambment of line eight of the second stanza with those of lines nine and ten of the third, help to illustrate this point. For example, the enjambment of these lines adds several layers to the interpretation of the poem. The first interpretation connects the mind-forged manacles with the chimney sweepers’ desperate cry for help. While in another instance, the phrase, “blackning Church” suggests that it is not just the buildings that are covered in soot but also the chimney sweepers whose soot-covered skins are often unrecognizable except for their cry that permeates the air and echoes in the speaker’s ear.

But the most important interpretation of the enjambment of lines eight through ten is that, if we remove the first two letters from the word ‘appall’ in line ten, we are left with the word pall, which is a cloth or shroud that is used to cover coffins for burial. Thus, the idea of a “blackning church” symbolizes the darkness of human cruelty, which helps to point the finger at the church for exploiting young children and in many cases standing by inert while they suffer and die. In addition, the use of the word “blood” in line twelve helps to cement this picture and creates this tension in the poem as we are not sure if the blood that runs down the palace wall comes from the chimney sweepers or the “hapless soldiers.” Either way, the fact that Blake uses synecdoche when he inserts the church to represent religious forces, and the palace to stand in for the monarchy or political forces demonstrate that regardless of whose blood it is, both entities are at fault for causing such suffering and misery. Furthermore, the poem seems to suggest that although every city, state, or country has its share of misery or struggles, what perpetuates the cycle of pain and suffering for London’s children is the blatant refusal to do anything to help them. And inaction results in weeping children. Also, as a genre that is meant to be read aloud, the poem reinforces its auditory nature by spelling out the word “hear” with the first letter that begins the first word of each of the four lines in stanza three, sounding the clarion call for all who should listen but do not, particularly those who have the religious and political power to save these children from exploitation and abuse.

Although the poem demonstrates how mind-forged manacles result in tragic consequences for the city’s children, its punctuation pattern is the one thing that disrupts these repressive manacles. For example, there are only two periods in the entire poem and they both occur in the first stanza along with one comma. Additionally, there are three commas in the second stanza, one in the penultimate stanza, and no end stops in the last stanza. In one sense, this punctuation style creates tension between the structure and the content of the poem as there is an inherent struggle between this looseness of the punctuation and the rigidity and somberness of the message the poem portrays. In another sense, the loosely patterned style of the poem matches the speaker’s aimless walk and the fact that each time he encounters a tragic scene, it disrupts what could have otherwise been a linear and pleasurable walk through London.

The canvass of suffering and weeping children that we see in the “London” poem prepares us for the weeping sweeper we encounter in “The Chimney Sweeper.” This poem, too, is a lyric poem with somewhat of an irregular rhyme scheme of aabbcacaefef, yet it is this irregularity that brings its paradoxical message to bear upon the reader with full effect. It opens with two speakers; the first is an unnamed witness who asks a question, and the other is the chimney sweeper who responds to it. Even though this unnamed speaker speaks only once throughout the course of the poem, there is the sense that he is still present and listening to the sweeper’s response. Could it be that this unnamed speaker is also wandering through London and sees this chimney sweeper weeping and then asks him about it? It is possible, but unlike the “London” poem, we are now getting the personal narrative of a single sweeper and the reason for his dire circumstances. Although the poem focuses on one chimney sweeper, his “weep, weep in notes of woe” not only mirrors the sound of his broom (Blake, line 2), it also echoes the “marks of weakness and marks of woe” from the “London” poem (Blake, line 4). It is the cry of this sweeper that links him to all the other crying sweepers, and as a result, it is the one thing that reconciles his humanity because he is otherwise unidentifiable. For instance, in the first line of the poem, the unnamed speaker describes the chimney sweeper as a “little black thing among the snow” not because he is cruel but rather to highlight that this child is robbed of his innocence and humanity. He is now a mere thing, an object that blends in with the harshness of his surroundings.

Similarly, the visible blackness that he bears is not because of his ethnic origin but because his skin is covered in the toxic soot that comes from sweeping the chimneys. Consequently, his blackness epitomizes the depravity perpetrated by society and his neglectful parents. When the unnamed speaker asks him, for example, “where are thy mother and father?” (Blake, line 3), the sweeper responds, “they are both gone up to the church to pray” (Blake, line 4). This response implies that his parents’ religious zeal blinds them to his suffering. In this sense, then, unlike the repression he and the other sweepers have to endure, his parents’ mind-forged manacles are self-imposed because they choose to have passion and zeal for the church but no compassion for the child that God has given them. If they love God whom they cannot see, then this love must be reflected in how they treat others, especially their weeping child. They fail to understand that religion starts at home and that God expects our first act of service to be to our families.

Comparably, the sweeper’s response also reveals his parents’ lack of perceptivity in seeing their child only through rose-colored glasses. He explains that because he was “happy upon the heath,” his parents did not recognize the woe he was experiencing (Blake, line 5). However, this paradoxical statement reveals the parents’ blindness because the word “happy” contrasts with the word “heath” which represents an uncultivated place that lacks the potential for growth or progress. So, although the sweeper sings, something is terribly wrong, and his song is only a mask for the woe he is experiencing on the inside. Yet the only way the sweeper can coexist in a family like this is to create a defense mechanism and pretend that he is happy in order to survive. With its message of survival in the midst of trauma, the poem transcends time and space because it speaks to children experiencing trauma today and challenges parents or guardians to pay close attention to their children. The truth is, we may think that all is well with our young children, but nothing could be farther from the truth as is the case with this chimney sweeper.

In an even more extreme and perverse case, “A Little Boy Lost” continues the theme of weeping children and shows how unmitigated cruelty can have dire consequences for children. The poem presents extreme cruelty by an authoritative figure in the church, but its tone seems more contemplative, and because of its contemplativeness, it stays with you long after you have read it. Even the poem’s meter contributes to its contemplativeness. Its lines reflect perfect iambic tetrameter, which makes it easy to understand as we relate to and reflect on the speaker’s circumstances. And although the poem has an irregular rhyme scheme, there is a pattern in this irregularity since all the stanzas have alternate lines that rhyme, which highlights the pattern of cruelty that Blake is chastising. There are six stanzas in the poem; the first two stanzas present the voice of a little boy, while a third-person point of view narrates the rest of the poem, allowing us to see two perspectives of cruel repression. It opens with a little boy who contemplates the idea of thought and man’s shortcomings in loving others more than himself. On the one hand, the little boy’s question can be interpreted as one posed to an earthly father, particularly because the -f is written in lowercase. As a child, he recognizes his insignificance just “like the little bird that picks up crumbs around the door” (Blake, line 8). It is not that the bird is special to anyone, but the idea here is that someone mindlessly drops crumbs that this animal now finds as food. Thus, the speaker is saying that if he, like the bird, is this insignificant how can he love his “father” or any of his “brothers more?” (Blake, line 5-6). His question shows his innocence and curiosity, which creates the perfect opportunity for this father figure or guardian to teach by example. On the other hand, the little boy’s question is especially important because the third stanza indicates that the boy could be posing the question to his heavenly Father. It is in this third stanza that we realize that the poem’s setting is a church. So, the little boy could have been at the confessional when the priest overhears his question and believes he is being blasphemous. Not surprisingly, the priest’s reaction demonstrates religious zeal that lacks love and kindness, both of which the boy needs to see demonstrated, which would in turn teach him that he can love the Lord and love others as himself. The priest, however, subjects the little boy to cruel and inhumane punishment by bound[ing] him in an iron chain / and burn[ing] him in a holy place” (Blake, line 20-21). Once again, we see the mind-forged manacles from the London poem on full display in this poem, showing how those who wield unchecked religious power become tyrannical figures who restrict individual thought and expression. This type of tyranny creates a space where religion is a self-contained mystery that not only creates vagabonds by neglecting the needy but is also the judge and executioner of those who question its authority. Here, the church is no longer a place for inquiry and open dialogue; instead, it is a place of repression and torture. Ultimately, the priest’s cruelty allows us to ask, how many other children have been burnt before in this “holy place” and other places like it? Furthermore, “the weeping parents wept in vain” is repeated twice almost like a refrain to show that not even their tears can deter the priest from his cruel intent (Blake, lines 18, 23). Moreover, the repetition links the parents’ weeping to the suffering child whom they are powerless to save. And because the poem ends on this note of powerlessness in the face of unmitigated evil, it, like the “London” and “The Chimney Sweeper” poems, does not resolve itself. In fact, it ends with a question, which intensifies the pain and suffering it communicates. Yet by asking, “are such things done on Albion’s shore,” the third-person narrator holds culpable not just those inside the church who “[admire] the priestly care,” but confronts the entire country for allowing these things to happen in the first place (Blake, lines 12, 24). Moreover, this haunting question becomes more poignant since the little boy is not lost because he is physically displaced from the centering of familiarity. Rather, he finds himself lost, castigated, and treated as if he were a vagabond because his question or curiosity cannot coexist with the mind-forged manacles that the church put in place to prohibit exactly what he seeks, reason and thought.

In a similar sense, “The Little Vagabond” poem questions religious authority but does so in a more humorous way. Even so, there is still an ominous quality to its lightheartedness. Indeed, I think this poem presents one of Blake’s most striking indictments of the church and its failure to care for those in need. The poem opens with a speaker who unashamedly sets up a contrast between the church and the alehouse. He tells his mother that the church is cold but the “Ale-house is healthy and pleasant & warm” (Blake, line 2). Because the church fails in its duty to provide warmth and acceptance, the little vagabond seeks these necessities in the alehouse, possibly among drunkards and prostitutes. And yet, the warmth and acceptance he receives in this place are much more welcoming than the “cold” rigidity he encounters at the church. The speaker’s use of the word “cold” has a double meaning because in a literal sense it could refer to the physical cold, indicating that the building lacks heat. In another sense, the word suggests that the religious people he encounters at the church are cold as they lack compassion, love, and generosity, which are characteristics of Christ. By the same token, when the speaker says if the church “would give us,” the weeping children—from chimney sweepers to youthful harlots, some “ale” he is not talking about the physical drink but is reminding us that the church lacks love (Blake, line 5). If only the church would give this human necessity, then, as the little vagabond humorously remarks, there would be no need for him or others like him to stray.

Although “The Little Vagabond” is strategically positioned in the Songs of Experience, its humorous tone and sing-song rhyme is reminiscent of the poems from the Songs of Innocence. All the stanzas of the poem, except for the first, have two sets of rhyming couplets. This musical quality of the couplets shows the speaker’s childlike nature as he presents his innocent argument in support of his views about why he prefers the alehouse more than the church. But even in his childlike innocence, the adult auditor, in this case, his mother, would recognize that only a dysfunctional atmosphere birthed by religious hypocrisy and cruelty could create the need for the little vagabond to go to the alehouse in the first place. Indeed, the alehouse is no place for a child, much less for him to express a preference for it. As a result, this poem reemphasizes that in the world of experience, perversion is the order of the day. It is a world of repression and mind-forged manacles that cause others to stray—creating so-called vagabonds—children who would much rather go to the alehouse than to a church.

“Comparably, “The Little Vagabond” also echoes sentiments from the “Chimney Sweeper” poem because the little vagabond indicates that extreme religious fervor at the expense of your children is a perversion of what Christianity should be. In his challenge of such perversions, the little vagabond reveals that “modest dame Lurch who is always at church / would not have bandy children nor fasting nor birch” (Blake, lines 11-12). The meaning of these lines is twofold. The first is that this woman, like the parents of the chimney sweeper, is always at church to the extent that she neglects her children. Her children suffer from malnutrition resulting in “bandy” legs, which is one of the symptoms of Ricketts disease. The other implication is the use of the word “birch, which could mean a whip used for punishment. Again, this so-called modest dame reveals the hypocrisy and irony of religion divorced from true Christian love and compassion; she is barely home and when she is there, she abuses her children.

Likewise, the “Holy Thursday” poem makes use of an apostrophe to address religious and political cruelty. Its particular style of asking questions and then answering them with a cold finality reinforces the harshness of a society bent on material gain while ignoring the plight of its children. England, this “rich and fruitful land” (Blake, line 2), reduces “babes” to “misery” and its “children” to “poverty.” With such a contradiction, the speaker is suggesting that for all its wealth, both imperial and industrial, it remains a poverty-stricken nation. Because if you want to judge the wealth of a nation, you have to look at how it cares for its children, women, and elderly citizens. Also, like “The Chimney Sweeper” and “A Little boy Lost” poems, “Holy Thursday” parodies its companion poem in Songs of Innocence. For example, the “Holy Thursday” poem from Songs of Innocence presents children who attend St Paul’s Cathedral for Holy Thursday service. The poem describes the children as the “flowers of London town!” (Blake, line 5). They “sit with a radiance all their own” as they “[raise] their innocent hands” and offer their harmonious song of praise (Blake, lines 6-8). In this “Holy Thursday” poem, they seem happy, unrestricted, and triumphant as they celebrate this joyous occasion. However, its companion poem in Experience offers us a closer look at the children. Through the lens of experience, we see that they are not happy, they are poverty-stricken. And because of their deplorable state, there is discord instead of harmony and their song is reduced to a “trembling cry” (Blake, line 5). Even the use of assonance reflected in several words with a long -o sound, both in the same line as well as in subsequent lines like the repetition of the word “song,” “so,” “poor,” and “poverty” all echo the children’s trembling cry and point to the disparity between what appears to be joy and what is indeed weeping and despair. Ultimately, the disparity comes down to who is looking at these children. If it is someone who cares about them then that person will see that the children are in dire straits. However, if it is someone who is blinded by religious hypocrisy and political negligence, then this person will pretend that the children are happy just like the parents of the chimney sweeper.

Overall, these poems cement Blake’s status as a social critic. They lay bare for all to see the deplorable condition of children in the English society during the time when Blake was writing. Therefore, the children we see in his poems represent real children with similar circumstances who could not escape the confines of child labor and abuse perpetrated by those with religious and political clout. And because the poems capture the reality of his society, they have the power to still speak to us, even as twenty-first-century readers. So, even though we may never experience what it feels like to be chimney sweepers, we empathize with the cruelty and suffering these children had to endure. Also, his poems are a powerful reminder to be perceptive about everything that concerns our children. We never know, we could be helping to protect our children or even other people’s children from all forms of exploitation, whether it is child labor or any other forms of child abuse.

Works Cited

Blake, William. “A Little Boy Lost.” Poetry Foundation. https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/a-little-boy-lost/. Accessed November 10, 2022

Blake, William. “Holy Thursday” from Songs of Innocence. Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43661/holy-thursday-twas-on-a-holy-thursday-their-innocent-faces-clean . Accessed November 10, 2022

Blake, William. “Holy Thursday.” from Songs of Experience. Poetry Foundation https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43662/holy-thursday-is-this-a-holy-thing-to-see. Accessed November, 10, 2022

Blake, William “London.” Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43673/london-56d222777e969 Accessed November 10, 2022

Blake, William. “The Chimney Sweeper.” From Songs of Experience. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43653/the-chimney-sweeper-a-little-black-thing-among-the-snow. Accessed November 10, 2022

Blake, William. “The Little Vagabond.” Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43672/the-little-vagabond. Accessed November 10, 2022

Ehrlich, Eugene., et tal. Oxford American Dictionary. Avon Books, 1980, p. 105

Montgomery, James. The Chimney-Sweeper’s Friend, and Climbing-Boy’s Album. Arranged by J. M. United Kingdom, n.p, 1824. Google Books. Accessed online November 27, 2022

Course: ENG 102 Literature and Composition

Assignment: Poetry Analysis

Instructor: John Christie

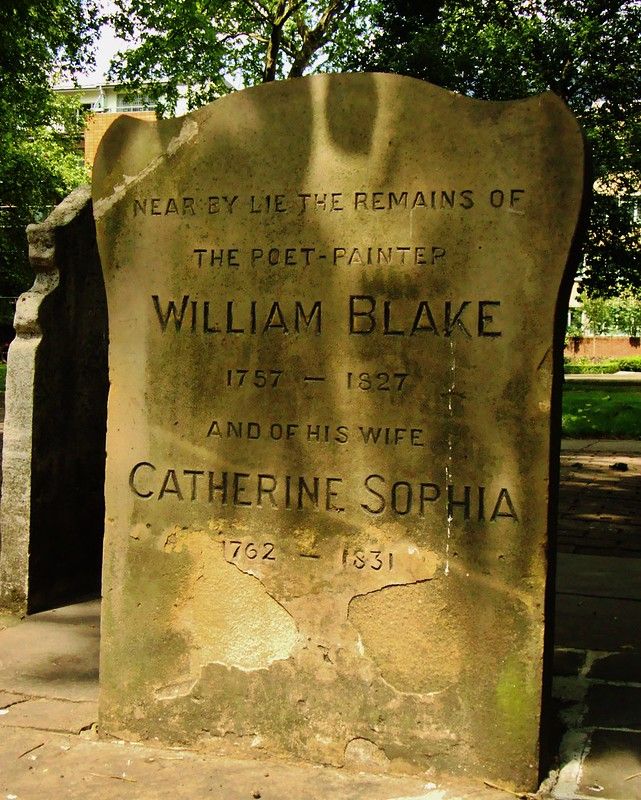

Photo credit: William Blake’s Grave, Bunhill Fields by Alex JD (Creative Commons)

Leave a comment